By Ewan Pearson

At this time of year, lots of wine is bought and pretty much all of it consumed; little would be bought for investment. There have also been some elections in the USA and a whole raft of exercises in evidence-base persuasion, both in the public domain and in private.

I recently surprised myself by selling a case of wine that I had bought some years earlier. I had intended to drink it but instead made a nice cash profit, but had nothing to drink. So I thought I would take a look at the use of evidence in these cases. Is it strong? Will it last? Does it pass the ‘smell test’? No, not the wine, but the strength of evidence-based arguments used in selling such cases. This paragraph just proves that puns are the second lowest form of wit… although still well above practical joke phone calls.

Evidence is fact; it can be checked and tested, verified or disputed by experimentation and observation. Just take the Higg’s Boson. Well, if you could take one…. Opinion is nothing like evidence. It is one person’s view. It usually predicts the future, which is notoriously hard to do accurately, and success mostly occurs by random chance rather than skill.

This is not investment advice! However as it is Christmas soon, I do want share some anecdotes about evidence given in support of an argument, and I will include one such argument given in favour of investing (instead of just drinking) wine.

You can make up your minds whether to invest, or to imbibe.

Buy wine, they ain’t making it any more

With my apologies to Mark Twain (this edition’s featured quotee), who said something similar, the case for investing in wine is made by most sellers of wine using a mixture of evidence and opinion.

Consider the following evidence from the wine merchants, Berry Brothers, on their website: “Whilst it is difficult to find totally accurate records and therefore data, prices for the very best wines have risen by an average of 15% per annum over the past 25 years.”

Yippee – if only I had bought some 25 years ago!

Deconstructing this gives you first a caveat condition (“it is difficult”), followed by a softener (“totally accurate”) which suggests the records are good enough, then a qualifier condition (“the very best wines”), then some data that is neatly rounded (15% and 25 years).

So is this strong evidence? No, I don’t think so, due to the conditions attached, but at least it can be checked. The trouble is that most of us won’t or can’t do that check.

Here’s the next piece of the argument: “It is undeniable that the best wines have proved to be sound long term investments over the past twenty years, though it is important to remember that one has to take the long term view.”

Hmmm, this argument is getting weaker. Now we are asked to accept an opinion (“it is undeniable”), which would not be true in every case, and also the caveat condition (“long term view”), which suggests if you time it wrongly, you could lose money, or make very little after holding an asset for some time.

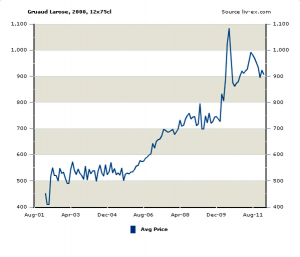

Berry Bros then show a price vs. year chart, supplied by Live-ex.com, of Chateau Gruaud Larose 2000, which shows (see below) an impressive line going from bottom left to top right, with a spike in 2010, and a price some 20% lower today. This is reinforced by notes that suggest you could have bought en primeur for £250 and sold for £900 now. Wow! Where do I sign?

Well, that seems a strong enough case, even though it is based only on historical data from a small sample.

Obama is bad for markets?

Here’s another example of persuasion: debunking myths. The Financial Times (4th November) carried a Lex Column article on the expected effect of a Democrat or Republican win in the US Elections on equity markets.

The article starts with a restatement of the ‘myth’ that might damage Obama’s chances of re-election: “Democratic Presidents are bad for US investors”.

The debunking is simple and quippish: “History does not bear out that judgement”, then the citing of data since Obama’s win in 2008 and generally since 1927, which supports this argument “even excluding the 1929 and 2008 crashes” (that happened it seems under the Republicans). All good stuff, but SO last century!

Like any good act of persuasion, the counterargument then kicks in: Roosevelt’s (Democrat) 2nd term was bad for investors (during WW2!!), and under Eisenhower (Republican) big gains were made. The author, James Mackintosh, then develops 4 arguments why shares might do better under Romney from here on (using speculation of future actions), then he argues against that then finishes with a flourish to suggest that perhaps it doesn’t matter who is in the White House, so preventing anyone from arguing against him. A neat trick, but thus largely useless in trying to tell what to do.

So you’re left with 10 minutes less of your life and no wiser, but a well-balanced and safe article has been written, and read. Papers have been sold.

The least useful aspect is that markets react so quickly to such new information that when you do try to act on any view formed, you either have to speculate in advance or get left way behind those slinky computer-trading algorithms.

What can you learn from this? Opinion is not evidence, the past does not predict the future, and you can’t predict it either. All persuasion is based on trust: Discuss.

Happy Christmas, and we do hope you enjoy all that time to speculate as you contemplate the contents of a fine wine. I know that I shall.