Christmas is a time for stories. The nativity is probably the most well-known story in Western culture. You know you will hear in the coming weeks, especially if you go to church. From priests to advertisers (John Lewis’ annual Christmas advert, anyone?) it seems that many know that we are highly receptive to the narrative form.

The context – what is a story?

Transmitting and receiving information in the form of a story is hardwired into us as human beings. As a species we were telling stories about the world long before science could clarify what the planets were or where wind came from.

We were telling stories before we had any language to do so – the first cave drawings were an explicit, if rudimentary, narrative. Even you were doing so: as a child you lived in a world of stories, those you read, and watched and the ones you made up!

The story of the nativity

But the balance has shifted. Although most of us still enjoy receiving stories (whether in the form of films, theatre, TV shows, novels, or even just elaborate jokes) we are much poorer at creating them ourselves. Our studies of economics, finance, management and other such valuable academic and commercial pursuits have reduced our capacity to use this method of conveying messages to the world.

A story is simply a personal way of attempting to make sense of the world for ourselves, and then sharing that insight: subsequently, listeners of said story instinctively assign meaning to the events described. So if you tell a story (with intention) to a client or to your stakeholders, you are ultimately sharing meaning in this highly personal way – and that is immensely powerful.

Some science – why do stories convey information so well?

“But wait”, you say, “I know GPB believe in blending science and art, so is there any evidential science backing up these claims about this ‘mythical art’ of storytelling?”

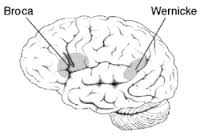

Actually, yes, there is. When we hear what might be termed ordinary or fact-based language (e.g. the usual key messages and bullet points etc.) the only areas of the brain that activated are the Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area – these two parts deal primarily with speaking and processing language.

Broca’s and Wernicke’s Areas

When we read or hear a story, many other areas of the brain are stimulated at the same time; namely, the sensory areas that would be involved if we were experiencing the events of that story for real. A number of studies have been done in this area pointing to this important conclusion.1

From this comparison it becomes easy to see how stories are very impactful tools from a cognitive point of view: the fact that many more sensory areas of the brain are working simultaneously allows for more effective framing, for creating real emotional connections and for increasing substantially the memorability and potency of the information you are presenting.

What’s your point Richard, how can I use this at work?

Stories help you present well: this can be formally selling or pitching a product or service, or selling an idea for buy-in from staff and key stakeholders. Here’s how you might go about building a story in:

1) Work out your intention: start with the objective in mind

This will be familiar to you from all our other advice when building content, and it’s key here too. It’s all about your audience, so what do you want your audience to think, feel or do at the end of it? Write this down and decide what style of narrative will best serve this end. Should it be about business specifically? Should it be serious or light-hearted? Should it be full of detail or only thinly detailed? What story type will help me to activate all those extra areas of the brain? Consider what Stephen Denning adroitly writes: “it needs to be kept steadily in mind that storytelling is a tool to achieve business purposes, not an end in itself” 2

2) Use an effective structure for your story

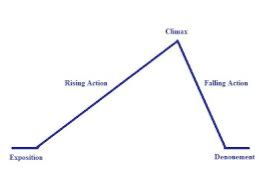

There are an infinite number of ways of telling a good story: Aristotle told the Greeks that 3 parts were best (beginning, middle, end), Horace told the Romans that 5 parts were more effective, the Japanese have Jo-ha-kyu (prelude-climax-break) and so on and so forth.

One classic Western version is Freytag’s Pyramid (above right), which may well work for you.

A highly summarised example of using it might go: Exposition (“I began working as a manager at this company in 2004…); Rising action (“We had many wonderful staff, but there was one senior guy in particular who I could never get through to”); Climax (“Then, at the summer off-site party that year, he pulled me aside…”); Falling Action (“After that talk at the off-site, I knew that he was right, so I tried to incorporate his advice in my work…) and finally Dénouement (“With a face of ice he turned to me and said, “You’re not a manager”. I froze. Then he smiled and said softly, “But now you can be a leader”.)

Freytag’s Pyramid

3) Believe it

There is nothing worse than watching someone emote, portraying an emotion in a theatrical manner; that is, importing feeling for effect because they don’t own or believe in what they are saying. This arouses our sensations of distrust and dislike. Why? Because we don’t like being lied to. A story doesn’t have to be real – but it does have to be truthful in its telling. Authenticity is key.

Wrap it up Richard, I’ve a party to get to…

As you go about your festive cheer, try to think about how well and why the stories around you are making an impact on those additional sensory areas of your brain. Now you have the idea, take storytelling back into the office and construct your own personal stories to help you sell you, your ideas, your products and/or your services.

That way you can turn to your colleagues at the Christmas party in a year from now, reflecting on the success of 2016, and say “It all began when I received GPB’s Christmas journal last year. Let me tell you the story of how stories helped me…”

By Richard Keith

References:

- Carlon Rush, Brianne, Science of storytelling: why and how to use it in your marketing, a summary of research from Psychology Today and others, published in the Guardian Newspaper Online, 28 August 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/media-network/media-network-blog/2014/aug/28/science-storytelling-digital-marketing, [Last accessed 1st December 2015].

- Denning, Stephen, (2006) Effective Storytelling: Strategic Business Narrative Techniques, in Strategy and Leadership, Vol 34, No.1, p.48