Current estimates in the scientific world suggest that less than 5% of our brain activity is conscious; some scientists put this figure as low as less than 1%. Cognitive research indicates that we take many decisions, make judgements, and reason without any need for conscious involvement (McGilchrist 2012 p.187)1.

In 1983 a now famous experiment took place, conducted by Benjamin Libet. Libet asked people to make a deliberate movement of their fingers and recorded the brain activity they displayed. He found that there was recordable cerebral activity (readiness potential) that clearly preceded the recorded time of the conscious intention to act.

This phenomenon had been witnessed before, but what Libet’s experiments showed was that the conscious preparation to move the finger occurred about 0.2 secs after the readiness potential had been recorded.

This experiment, along with subsequent others, cast doubt on the long-held belief that we have full volition over our actions.

Yet the experiment showed that although the unconscious activity of the brain initiated the action, there is clearly still a role for the conscious part of the brain to play. Libet sums this up:

“The role of conscious free will would be, then, not to initiate a voluntary act, but rather to control whether the act takes place. We may view the unconscious initiatives for voluntary actions as ‘bubbling up’ in the brain. The conscious-will then selects which of these initiatives may go forward to an action or which ones to veto and abort, with no act appearing” (Libet 1999 p.54)2

It is overstating things to conclude from this that we do not have any free will. Yet what we must guard against is the equally simplistic view that we make decisions based only – or even mostly? – on information of which we are conscious.

To use a simile, it’s as if our subconscious has worked out possible destinations and the corresponding airlines before our conscious brain even decides that we want to go on holiday.

There are a number of ways that this idea affects your presentations, pitches and business development. Let us look at one related part of this – the Primacy of Affect.

Primacy of Affect suggests that emotions (affect) can be processed more readily than (faster) actions. It influences whether or not we like something, which is exactly what your audience and/or clients decide when you present or pitch to them. A lot of this decision-making is performed in the subconscious.

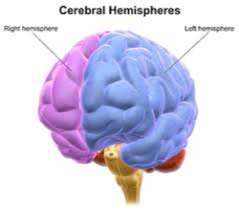

In short, research has shown that the right hemisphere of the brain is the main location of our affective assessment of something as a whole; this judgement occurs before the left hemisphere performs most of the cognitive analysis of the various parts that make up that whole.

The left hemisphere then tells a particular story about how a decision has been made, suggesting that all the logical parts were the drivers of the choice.

This information is then backdated into how we appreciate the decision so we can rest easy at night believing we are the rational, sensible decision makers we have always been. Unfortunately this is rarely the case.

Affect is a way of relating and attending to the world. It is important to understand

that emotion is part of this, but not all of it. Emotion is more central to our being than cognition, although we would like to believe otherwise.

“Feeling is not just an add on, a flavoured coating for thought: it is the heart of our being and reason emanates from that central core of emotions, in an attempt to limit and direct them, rather than the other way around” (McGilchrist 2012 p.185)1

How someone feels about you, then, is a hugely important element to tap into when we want to persuade, as many scientists now believe it is the origin of reason: “Feeling came, and comes, first, and reason emerged from it.” (McGilchist 2012 p.185).

More recent research is exploring this. For example, Amy Cuddy has argued that although we are keen to demonstrate competence when we interact in the professional world, we should firstly focus on demonstrating our trustworthiness and warmth. From an evolutionary point of view this makes sense. Cuddy writes:

“Why do we prioritise warmth over competence? Because from an evolutionary perspective, it is more crucial to our survival to know whether a person deserves our trust. …. We do value people who are competent, especially in circumstances where that trait is valued, but we only notice that after we’ve judged their trustworthiness” (Cuddy 20153)

It is probably not a surprise for you to read that how your audience/clients/investors feel about you is hugely important when they make decisions.

What may be more surprising is that most of their feelings are likely to be subconscious; their feeling about you is likely formed in the very early stages of any interactions and based on numerous factors that they are rarely fully aware of; and that whilst you may be desperate to show how good you are at your job, they are likely prioritising other aspects of your personality such as whether they trust you and like you.

Whilst it’s essential to be good at what you do and to be highly articulate about the value you add, if you neglect all the other cogs whirring deep within the brains of your counterparties, you may find yourself much less persuasive that you’d like to be.

Sources:

- McGilchrist, Iain. 2012. The Master and his Emissary: the Divided Brain and the making of the Western world (Yale University Press: New Haven).

- Libet, Benjamin. 1999. ‘Do we have free will?’, Journal of consciousness studies, 6: 47-57.

- Cuddy, Amy. 2015. Presence: Bringing your boldest self to your biggest challenges (Hachette UK).

Download a pdf of the article here: The brain in our decisions