Persuasive Communication: Examples from Famous Authors

Des takes persuasion lessons from Austen and Dickens. The latter offers us a famously topical festive example

A recent re-reading of Jane Austen’s ‘Persuasion’1 has prompted discussions with my GPB colleagues on its title and subject matter. I’ll briefly share relevant reflections on that with you here before turning to a more festive parallel.

Austen’s original and anodyne working title was ‘The Elliots’. It was only when published, six months after Austen’s death, that the novel gained the title her brother Henry provided, by which we now know it. Despite this, one of her preoccupations specifically concerned one’s influence over others, as Henry’s title suggests. She explores how status and standing affect an individual’s power of persuasion. Austen depicts the potential dangers of exerting influence (sometimes unintentionally) on others – and the life-changing consequences and responsibilities arising from such coercion, however well-intentioned.

Austen’s original and anodyne working title was ‘The Elliots’. It was only when published, six months after Austen’s death, that the novel gained the title her brother Henry provided, by which we now know it. Despite this, one of her preoccupations specifically concerned one’s influence over others, as Henry’s title suggests. She explores how status and standing affect an individual’s power of persuasion. Austen depicts the potential dangers of exerting influence (sometimes unintentionally) on others – and the life-changing consequences and responsibilities arising from such coercion, however well-intentioned.

The introduction to my Penguin edition2 suggests that misgivings about her own unintended, real-life influence over her niece’s life choices provided the artistic motivation. Austen warns us to wield our persuasive power warily, and to consider the potentially damaging effects on others of doing so. Her theme predates and paraphrases the adage since popularised by Spiderman in Marvel Comics and in their recent film adaptations: the “Peter Parker principle” – ‘With great (persuasive) power comes great responsibility’3.

Her concerns may feel less relevant to a modern audience, however. Given that the power afforded automatically to an influencer, simply by their status (see also part 1 of Aristotle’s’ Ethos), appears to have reduced dramatically since Austen’s time. That could be one reason why so many senior figures and organisations seek advice on Persuasive Communication from GPB.

But who DOES successfully persuade us nowadays—and how? We’ve learned no longer to believe much that’s said by briefed politicians or other formal spokespersons, for instance. Systematic deference for the elderly has been eroded, at least in the West. The medical world has lost its relatively unchallengeable status – as anti-vaxxers have demonstrated. Whereas one perhaps rather unlikely person who wields strong persuasive influence globally is a diminutive Swedish teenager with Asperger’s Syndrome.

But who DOES successfully persuade us nowadays—and how? We’ve learned no longer to believe much that’s said by briefed politicians or other formal spokespersons, for instance. Systematic deference for the elderly has been eroded, at least in the West. The medical world has lost its relatively unchallengeable status – as anti-vaxxers have demonstrated. Whereas one perhaps rather unlikely person who wields strong persuasive influence globally is a diminutive Swedish teenager with Asperger’s Syndrome.

Jane Austen might well have been astonished at Greta Thunberg’s persuasive appeal and effectiveness. Since it fails to follow the model of influence she depicted and felt she understood so well. At GPB, we’re less surprised. If you want to persuade others nowadays, typically you must earn that right. And Thunberg earns it through several powerful means, in a non-native language. Her approach has helped gain her three nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize, so far. Why is she so effective? Perhaps because:

1) Greta Thunberg seems well-informed and passionate about her climate activism for one so young.

2) She focuses on a small number of Key Messages (arguably just one!) using carefully selected powerful evidence and rhetoric in support.

3) She’s not afraid to communicate honestly about her beliefs and experiences, and she relates positively to a broad spectrum of her audience.

The success of this approach is so very difficult to compete against that Thunberg’s detractors often resort to ‘ugly personal attacks’4, rather than directly addressing the subject of her activism. She shows us a powerful example of persuasion in action today.

Since Austen’s novel is hardly an iconic Christmas tale, let’s now turn our attention to a more topical take on persuasion. One that’s more redolent of the season of good will, cooked goose, holly wreaths, Christmas spirits (plural) and much more, besides. It’s another story depicting the power of persuading others. I’m referring to Charles Dickens’s ‘A Christmas Carol’5, in which Ebenezer Scrooge is famously visited by four philanthropic ghosts one Christmas Eve, intent on saving his soul. Each hopes to influence the misanthropic miser to open his heart, and his purse, to those less fortunate.

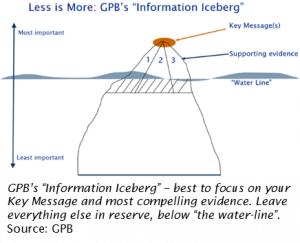

As though in keeping with GPB’s guidance, each spirit provides Scrooge with powerful evidence (i.e. of the negative impacts of his lifestyle and choices). Using just a few Key Messages, each one selectively focuses Scrooge’s attention towards the top of what GPB terms the “Iceberg of Information” (where only their most relevant and compelling evidence is shared, see image on next page). And while Scrooge remains impervious to their warnings at first (“Bah! Humbug!“), as the accumulated force of their evidence becomes ever more affecting, he eventually sees the error of his miserable ways.

It’s worth remembering, however, that Scrooge’s epiphany famously requires supernatural terror for a successful intervention. Ebenezer’ misanthropy has remained impenetrable, over several years, to the persistent human persuasive efforts of his nephew, Fred. Rather than echoing Austen’s concerns about the dangers of persuasion, Dickens’s key message is about the fallibility of human intervention and influence, when not specifically tailored to the audience, particularly so in the absence of compelling supporting evidence.

That’s a key message which GPB fully endorses. Dickens’s Christmas spirits must bring powerful, opinion-changing evidence, to stir stubbornly stony Scrooge, until – and only at the very end – ‘his own heart laughed’6.

So, when you find yourself in similar shoes to those of Jacob Marley’s ghost, needing to persuade an awkward audience, GPB’s “spirited” advice might include the following:

- Consider your audience

- Focus on your primary objective

- Prepare just a few Key Messages, appropriate to both the audience and your aim

- Research and employ the most independent, free and quick-to-access evidence in support of case

- Use just a few striking, memorable visual aids – e.g. perhaps some helpful ghosts, if you’ve any to hand.

If we can learn from these pointers, and from Austen and Dickens, then ’God Bless Us, Every One!’7 Implementing them should result in a more persuasive and prosperous New Year.

By Des Harney

References:

- ‘Persuasion’ (1817) by Jane Austen

- ibid: The Penguin Classics edition (1998) – introduction, by Professor Dame Gillian Beer, University of Cambridge

- Marvel Comics, Spiderman – from Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962) onwards: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spider-Man

- Chakrabortty, Aditya in The Guardian (1 May 2019) “The hounding of Greta Thunberg is proof that the right has run out of ideas”

- ‘A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas.’ (1843) by Charles Dickens

- ibid: ‘Stave Five’ (the final chapter)

- ibid: the final words of Tiny Tim (‘who did NOT die’) and which end the book.

- Ciarán Hinds and Amanda Root in BBC TV’s 1995 adaptation – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persuasion_(1995_film)

- Greta Thunberg, in 2020 – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greta_Thunberg

- Ebenezer Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present— https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Christmas_Carol#/media/File:Scrooges_third_visitor-John_Leech,1843.jpg

- A Christmas Carol book— https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Christmas_Carol#/media/File:Charles_Dickens-A_Christmas_Carol-Title_page-First_edition_1843.jpg)