“If you use words that the viewer has to process, then they will miss the next three to six words that you say.” This is a quote from Scott Chisholm who, it appears, is the man who coached Alastair Darling’s performance in the first televised debate against Alec Salmond on Scottish independence.

Alastair, ‘as dry as a bone’ Darling produced a performance in the first debate that was robust, witty and with flashes of emotion. Salmond’s theatrical style by contrast was, in my opinion, wrong-footed. True, the second debate was a reversal of fortunes although Darling did score some hits. Scott Chisholm’s advice goes on to say you have to pitch as though your audience are ten year olds. Is he right? Does this apply to business presentations? Well, Chisholm is referring to the rock and roll of a TV debate, and this is not quite the same as a business presentation. But he does point out that the Financial Times uses language that could be understood by a literate 12 year old. And we would agree with that approach.

Again and again we ask presenters to simplify what they are saying. The great majority over-complicate their story. Most will admit this but find it hard to get to the right place. Some say that the audience, who have knowledge of the subject, don’t want to be patronised. We completely agree!

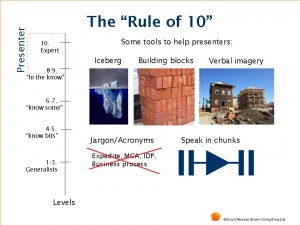

The start point then is to look at knowledge profiles of your audience. We call this the ‘The Rule of Ten.’

Audience Knowledge – A scale of 1-10:

Level 10. You, as the presenter are the expert and so you are at level 10. You know the subject well, in detail; when talking to close colleagues you may use common jargon laden language and various shortcuts. They are also experts so will understand. But brevity is still preferred.

Level 8-9. These are people in the know. They understand almost all of the jargon and business terms, and are used to seeing the sort of slides you may use. But you can still confuse them with too much detail and a lack of imagery. They may remember what you said afterwards. Lots of information but no message.

Level 6-7. These are people in the business but are not specifically in your area. They understand some but not all of the detail but will take longer to process ideas.

Level 4-5. These are people who are not experts in your area. Jargon and detail confuse. They take longer to process complexity. These people are often senior and often decision makers. These also make up most of the typical audience.

Level 1-3. These are people outside your business with low-level and varying knowledge. Most will be intelligent executives able to process complex and subtle ideas, if properly briefed. They may also be the most important as they may be the ones who have to be persuaded by your presentation. Here are a few of our tools that help presenters in such situations:

Iceberg. Use just the tip of it. This simple concept is about sticking to your key points with minimal elaboration. Stay above the waterline. A simple test is to imagine you only have 60 seconds to get key points across – what would they be? In turn this means cutting out unnecessary detail. Do they need a continuous flow of slides? This applies to all levels 1-10.

Basic Building Block. For levels 1-5 there is an absolute need to put in a basic building block that all can understand, pitched for that 12 year old. A great example is the YouTube series by Paddy Hirsch. He explains complex financial matters very well. For example the Yield Curve. I might have nodded wisely but on hearing the term I actually had little idea what it was until I watched 4 mins of Paddy Hirsch on YouTube. I am still not an expert but now I understand the concept well enough to take on more complex detail.

Use of verbal imagery. Key points are fine but they can be abstract; imagery helps the listener to create an image quickly in their brain that can be remembered long afterwards. Paddy Hirsch, describing private equity, uses the analogy of a group of investors buying a house. He develops the process on a flip chart and towards the end of his entertaining 4 minute talk makes a number of quite complex points; the high level of imagery really helps to make it all stick. So use “Stickies”, as we call them.

Remove jargon and acronyms. All corporations use them. The military do it. The lawyers do it. Who doesn’t do it! (Ans: good journalists). Those of us not in the know feel undermined as we struggle to make sense of what we hear. We may puzzle it out from the overall context, but we fall way behind and fail to register the key points as we spend too much time translating. So err on the side of caution and assume that levels 1-7 will not understand your pet acronym or the local jargon.

Speak in chunks. This is about pace; it is an easy concept in theory but harder in practice. Ideas need to be delivered in chunks with distinct pauses at the end of each idea to enable the audience not just to listen but also to have time to process the ideas. How long is a chunk? Maybe a single phrase, or a few sentences – up to 30 words. Then pause. The key, with a longer section, is that you are clear about what the final words are. If not then you start to add umms and errs. Whenever I hear an idea ending with the word ‘AND’ I know they are not speaking in chunks. I recently heard a QC (Queen’s Counsel – a top level UK advocate) end a statement with this: “At the heart of this case is a simple and serious injustice to a 96 year old victim.” This is chunking.

To Sum Up. All presenters fall victim to over-complicating presentations, so it takes skill and effort to ensure that key points can be detected, understood, and made compelling… and that key points can easily be remembered afterwards.

Alastair Grant